Holocaust Education & Genocide Preventation

A Distinct History, a Universal Message

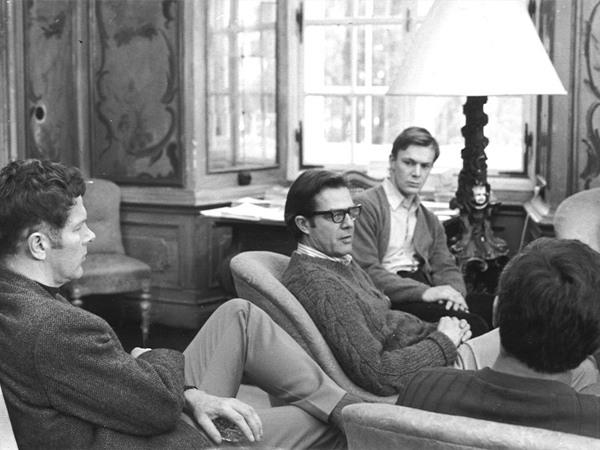

For three days, at a palace once home to the local Nazi party leader, experts from across the globe considered the value of Holocaust education in a global context at a symposium hosted by Salzburg Global and the US Holocaust Memorial Museum. They proved the Holocaust is more than just a European or Jewish experience.

Aloys Mahwa was not in Rwanda when the genocide happened. He and his family were just 10 minutes over the border in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo. And while Mahwa and his immediate family had escaped the 100 days of killing, they returned home to find his extended family had not been so lucky.

“My father lost almost 80 per cent of his brothers and sisters. It was a very huge family of ten children. And also I lost aunts, nephews and cousins,” explains Mahwa, now executive director and researcher at the Interdisciplinary Genocide Studies Center in the Rwandan capital, Kigali.

Knowing the exact times and places his family were slaughtered is difficult. “There is work to do in terms of document[ing] the members of our family – their ages, when they were killed, the circumstances… It’s a very frustrating history,” he adds.

But with its own genocidal past, with which it is still struggling to come to terms, especially with regards to educating future generations about the atrocities that took place, why is it important for Rwanda to learn about the Holocaust, which is widely considered a primarily European and Jewish experience?

“First of all we want to understand our own genocide… Up until now, people are facing some realities like...victims living with perpetrators, orphans, survivors from genocide now are [having] children.

“So that’s why we’re trying to be open and that’s why we’re learning about the Holocaust. We expect support from them [teachers of the Holocaust] because they have a huge experience and a long history, materials, personal engagement, and that’s very, very meaningful for us,” says Mahwa.

Rwanda is not the only country not traditionally associated with the Holocaust to recognize this value of educating future generations.

There are other Histories of suffering but also other Histories of moving beyond Trauma.

The Salzburg Initiative on Holocaust Education and Genocide Prevention, a multiyear program launched in 2010 in cooperation with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, focuses on the activities of educators in countries that are not one of the 36 member states of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA).

In 2012, participants came from countries as diverse as Mexico and South Korea, as well as countries that have suffered their own ethnic violence and genocides, such as Cambodia and Armenia, together with countries more commonly associated with Holocaust education, research and commemoration, like Germany, Austria, and the USA, all of which are members of IHRA. These participants came to learn not only how they can better teach about the Holocaust and the connected issues of human rights, shared history, prejudice, state and citizen responsibility and the role of democracy, but also how this will help them to better understand and learn about and from their own countries’ violent pasts.

For teachers in South Africa, a country ravaged by years of racial segregation and violence, the Holocaust can provide a theoretical framework that can be used to help understand the Apartheid regime, which might otherwise prove too personal and “painful,” explains Tracey Peterson, education director of the Cape Town Holocaust Centre.

“ The history of the Holocaust ... illuminates our history in quite direct ways,” explains the former high school history teacher.

“The most obvious connection is the fact that in order to understand what happens in the Holocaust, you need to understand the construction of the state under Nazi rule and, in many ways, what the Nazi government does is what happens in South Africa under the Apartheid government; segregation had existed in South Africa before Apartheid but what the Apartheid government does is consolidates rules, introduces new laws and really concerts all other efforts to divide people according to made-up categories. So South Africans find a lot of resonance in that part of the history of the Holocaust.

“But I think more than that, I think what it also does is remind South Africans that there are in some ways other histories of suffering, but also other histories of moving beyond that trauma, and so I think it can be instructive on that level.”

Cambodia, too, is using the Holocaust to illustrate that it is not only its own country that has a troubled past.

“In Cambodia, I think it is very good to introduce learning about the Holocaust because the majority do not know what happened in World War II or the Holocaust. So there is an effort from [the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam)] in trying to show the Cambodians that genocide does not happen only in their country but it has also happened in other places,” says Sayana Ser, team leader, Student Outreach and Cham Oral History Project, at the DC-Cam.

“When they learn about the Holocaust, it can help them [to know] that it has not only happened in their own country,” says Ser. In the spirit of a thorough exchange of global knowledge and experience, not only have the Rwandan and Cambodian participants learned from their international colleagues who have been teaching about the Holocaust, but they have also been sharing their own teaching experiences with each other.

“We stick to the Facts, not Emotions. We are not going to invent history.”

In Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge genocide did not appear in school history books until the 1990s and even then, this was limited to a small number of paragraphs before being removed completely for political reasons in 1998.

The DC-Cam has been working with both local and international experts in law, anthropology and political science to design a new curriculum for genocide studies and human rights in the country. A text book was published in 2007 and in 2009 the teachers’ manual was also published.

Through these new teaching materials, Ser hopes not only can Cambodians receive a fuller teaching of their nation’s history, but also move beyond the typically vengeful and retributive history that had previously been taught in schools.

“We stick to the facts, not emotions,” says Ser. It is this example that the Rwandans now also hope to incorporate into the teaching of their own genocide.

“We are not going to invent history when we are teaching genocide in a class,” says Mahwa.

“We’re not choosing the same materials... but adopt[ing] textbooks. For example, picture books – these can help. In the post- Cambodia [situation] they’re trying to use this textbook for teachers and students.”

Beyond countries that have faced their own genocides and ethnic conf lict, the Holocaust is also being taught elsewhere, primarily through the prism of human rights, democracy and peace education, and also in the effort to prevent such atrocities from happening again – something Mahwa wishes had existed in Rwanda, pre-1994.

“Dreadful things happen when Human Rights are not respected.”

“I was touched by the countries that [have] not experienced genocide and who are engaged to understand Holocaust, in a perspective of preventing it,” says Mahwa, “... They can prevent genocide by teaching their students about Holocaust. So that touched me in the way that if we had profited from that experience before, maybe the genocide would not have happened in our context, in Rwanda.”

Another country not traditionally associated with the Holocaust that is taking its first tentative steps into Holocaust education is Turkey, which has held observer status to IHRA since 2008 – so far, the only Muslim-majority country to do so. It is against this backdrop that the first pilot project on Holocaust education, led by the Netherlands-based Anne Frank House and the USHMM, has been recently launched in the country, and representatives of the project joined their peers at Salzburg Global Seminar to share their approach to the subject.

However, in contrast to those from some of the countries taking part that also have their own painful national pasts, the education initiative in Turkey is focusing solely on the Holocaust, and not introducing links to the country’s own still very controversial history over the treatment of Armenians during the Ottoman Empire Reign.

Although they do not address the Turkish- Armenian issue, parts of the education projects have focused on human rights, encouraging teenagers and young people to make videos debating certain aspects of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – written in the wake of the Holocaust – and applying these values to modern Turkey.

One area of the world where Holocaust education is not being viewed through the prism of human rights education, however, is China. Many of Glenn Timmermans’ students only have a passing knowledge of the Holocaust, mostly gleaned from Hollywood movies such as Schindler’s List. But this has not deterred the British professor in the Department of English at the University of Macau.

“I think the Holocaust is a subject that really is universal,” says Timmermans. “Even though it is a European Jewish experience, it is an earthquake in Western conscientiousness, and I think that if people want to learn about all the glories of the West, they need to know about some of the negative aspects of the West,” he explains. “As a literature professor, I think it is very important that my students know that if they want to know about Western culture, Western literature, they must know about this event.”

“But we have to be wary of using terms like ‘human rights’... As soon as you try and teach, as discussed at this conference, ‘how do we link it to human rights?’ – it’s potentially problematic. If we can introduce it through straight history, straight literature, then get people to cover the issues and perhaps draw their own conclusions without us having to prompt them, that would be the most effective way,” concludes Timmermans.

But whether taught through the prism of human rights, democracy and peace education, or in order to help a society recover from its own trauma, or through “straight history, straight literature” leading students to make their own conclusions, ultimately, the Salzburg Global Seminar session on Learning from the Past: Global Perspectives on Holocaust Education could be summarized by the late night fireside chat statement made by Ghanaian professor, Edward Kissi, a specialist in African perspectives on the Holocaust and associate professor of Africana Studies at the University of South Florida, USA.

“The Holocaust may have a distinct history, but it has a universal message: dreadful things happen when human rights are not respected.”

For further information, please see: holocaust.SalzburgGlobal.org