Mellon Fellow Community Initiative

An Unlikely Constellation of Partners

Historically Black Colleges and Universities and the Appalachian College Association, member institutions of which serve predominantly white students, do not seem like the most obvious of partners. But this did not stop them from coming together to transform their schools into sites of global citizenship through the Salzburg Global Seminar-led, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation-funded Mellon Fellow Community Initiative.

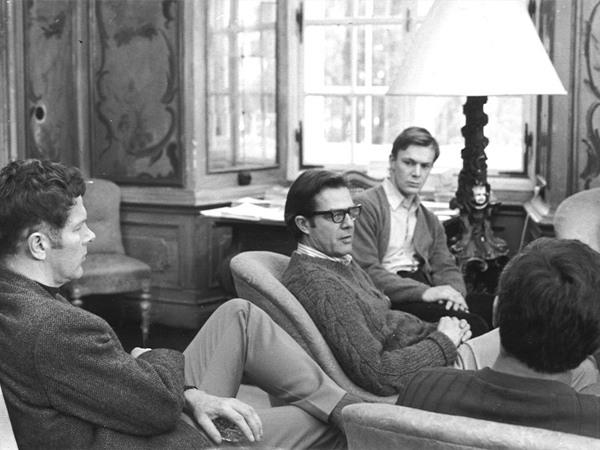

When in January 2008, the first group of 45 faculty and administrators of the Mellon Fellow Community Initiative convened in Salzburg, it was not anticipated that the seeds were being planted for a much larger and ambitious project than a single one-off session.

Despite structural similarities between the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and the Appalachian College Association (ACA) schools—their liberal arts approach, small size, location south of the Mason-Dixon Line, turn of the 20th century founding, religious roots and affiliations, and most importantly, their student populations that are traditionally underrepresented in the US higher education system including many first-generation college students— everyone who entered the meeting room for the first session immediately noticed an unmistakable difference between the teams of participants of the 15 colleges and universities: the difference of race. It may have been less clear in their minds what they could learn from each other.

This was the starting point of the MFCI, and the question was if and how the ensuing discussions about a lofty topic such as global citizenship as a cornerstone for 21st century undergraduate education would change the dynamics of the interactions between ACA and HBCU representatives, individually, and institutionally.

By the time this five-year-long project had concluded, the lessons to be learned from each other had become abundantly clear; global education had served as a bridge and a force to connect the ACA and HBCU institutions, the work that they do, and the students and communities that they serve.

One of the common misunderstandings about global education is the presumption that being a global citizen starts and ends with traveling to distant countries, an opportunity often not afforded the students or faculty of smaller institutions like HBCUs and ACAs. But global education is not only – and not even primarily – about traveling to other parts of the world. “Globalization at home” is about teaching and modeling inclusion, diversity and reciprocity in the context of how one relates to an increasingly interdependent world. It is as much about crossing national or state borders as it is about crossing “borders of the mind” by reaching out to “otherness.” Global education is about educating students to develop the life (and work) skills necessary for the 21st century. It is about learning how to make the cultural diversity, which is found not only far from home but also increasingly in our backyards, an asset from which one can benefit rather than solely a challenge to overcome.

This seemingly “unlikely constellation of partners” of ACAs and HBCUs offers a unique opportunity to make “globalization at home” and “citizenship without borders” a powerful and tangible learning experience for their students, and in the process make a significant contribution to the ongoing discussion about diversity and global education in US higher education.

Based on the positive feedback of the experience of that the first group of 15 colleges and universities, a second cohort of 11 ACA and HBCU institutions and then a third cohort of ten more institutions joined the MFCI.

Over the course of two years for the three cohorts, each institution’s initial global education project plan (the strength of which had determined their successful application to the initiative) was reviewed, revised, refined and expanded, translated into coherent and realistic action steps, and rolled out for implementation, thus beginning the weaving of global education into the fabric of the respective colleges and universities.

Activities expanded beyond the faculty and administrator sessions in Salzburg to include a student session on global citizenship also at Schloss Leopoldskron, and shorter workshops on specific topics related to global education held on the campuses of partner institutions in the US. These varied activities enabled the network capacity of the MFCI to grow considerably, both in terms of the extensity of its membership and the intensity of exchange and mutual learning.

“Over five years, the MFCI grew into a strong network of nearly 250 faculty, administrators, and students at 36 institutions engaged in global education activities at and across institutions,” explains Salzburg Global Director of Education, Jochen Fried.

“Although this may not have been part of the original plan, everyone involved in the MFCI quickly recognized its unique potential. As a result of a deep commitment to a common cause and roughly equal doses of intentional design and serendipity, this Initiative, with its modest beginnings, has transformed individuals and left lasting legacies at the institutions involved.”

For the full MFCI report, please see: www.SalzburgGlobal.org/go/MFCIreport

For further information on the Global Citizenship Program, please see: gcp.SalzburgGlobal.org